Measure-Rewind-Measure Paper Reading 1 - FO transform under ROM

This series of articles will follow the paper Measure-Rewind-Measure: Tighter Quantum Random Oracle Model Proofs for One-Way to Hiding and CCA Security to summarise the up-to-date research on IND-CCA security under quantum random oracle model (QROM).

I intended to write this series for better understanding my supervisors' paper, but it turned out that I actually can use this paper to walk through this research topic. By the way, I think this is exactly what a good paper can bring to you: a novel technique, with clear explanation, that can lead you going through a whole topic, also with several open problems at the end.

Disclaimer: I took a lot of text directly from my reference materials. They were not cited in a strict academic citation way. Because I think they have been clear enough and there's no need to paraphrase them again. I'll list the reference at the end, though.

In Part 1, I will walk through the definitions of the followings:

- Random Oracle Model

- CPA, CCA, Indistinguishability

- Fujisaki-Okamoto Transform under ROM

I will explain QROM and FO Transform under QROM as a short survey in Part 2.

Random Oracle Model

Random Oracle Model (ROM) is a heuristic tool for modelling a practical hash function \(H\) as a truly random function \(\mathcal{O} \in \mathsf{Funcs}[\mathcal{M, T}]\), where \(\mathsf{Funcs}[\mathcal{M, T}]\) is a set containing all functions that map an element from \(\mathcal{M}\) to \(\mathcal{T}\).

In other words, suppose we have a cryptographic scheme \(\mathcal{S}\) that contains a hash function \(H:\mathcal{M} \rightarrow \mathcal{T}\). If \(\mathcal{S}\) uses \(H\) as a black box, then we say \(H\) is used as an oracle. Simply speaking, we replace the hash function \(H\) in security property games by \(\mathcal{O}\).

Therefore, suppose we are interested in security property X of scheme \(\mathcal{S}\), then the game-based advantage of an adversary \(\mathcal{A}\) is \(\text{X}\mathsf{adv}[\mathcal{A, S}]\). The security of \(\mathcal{S}\) wrt to property X means that \(\text{X}\mathsf{adv}[\mathcal{A, S}]\) is negligible for all efficient \(\mathcal{A}\).

If we want to investigate the security of \(\mathcal{S}\) in ROM, the game is modified by this way:

- Challenger: randomly chooses \(\mathcal{O} \in \mathsf{Funcs}[\mathcal{M, T}]\).

- \(\mathcal{A}\): chooses random oracle queries, say \(m\in \mathcal{M}\), to the challenger.

- Challenger: evaluates \(t = \mathcal{O}(m)\).

- \(\mathcal{A}\): repeats this process with wanted number of RO queries.

We call this advantage in ROM as \(\text{X}\mathsf{adv}^{RO}[\mathcal{A, S}]\).

The advantage of using ROM in security proof is that it rules out generic attacks. Thus, when balancing applicability and security, security proofs under ROM are more often adapted. But ROM doesn't guarantee security for a specific hash function, since it's only heuristic.

CPA, CCA, Indistinguishability

Computationally indistinguishability

Attack Game: Distinguish \(P_0\) from \(P_1\)

For given probability distributions \(P_0\) and \(P_1\) over finite set \(\mathcal{R}\), and for an adversary \(\mathcal{A}\), we define 2 experiments, \(E_0\) and \(E_1\). For \(b = 0, 1\), we define:

\(E_b\):

- Challenger: computes \(x\) as follows: \(x \stackrel{\$}{\longleftarrow} P_b\), and sends \(x\) to \(\mathcal{A}\).

- \(\mathcal{A}\): receives \(x\), then computes and outputs a bit \(\hat{b} \in \{0,1\}\).

Let \(W_b\) be the event that \(\mathcal{A}\) outputs \(1\) in \(E_b\). We define \(\mathcal{A}\)'s advantage wrt \(P_0, P_1\) as below: \[ \text{Dist}\mathsf{adv}[\mathcal{A}, P_0, P_1] := | \Pr [W_0] - \Pr [W_1] |. \]

Definition: Computational indistinguishability

Distributions \(P_0, P_1\) are called computationally indistinguishable if the value \(\text{Dist}\mathsf{adv}[\mathcal{A}, P_0, P_1]\) is negligible for all efficient adversaries \(\mathcal{A}\).

IND-CPA security

Attack Game: IND-CPA security

For a given cipher \(\mathcal{E} = (E, D)\), defined over \((\mathcal{K, M, C})\), and for an adversary \(\mathcal{A}\), we define 2 experiments \(E_b\). For \(b = 0, 1\), we define:

\(E_b\):

- Challenger: selects \(k \stackrel{\$}{\longleftarrow} \mathcal{K}\).

- \(\mathcal{A}\): submits sequential encryption queries to the challenger. The \(i\)th query is a pair of messages \((m_{i0}, m_{i1})\in \mathcal{M}\) with same length.

- Challenger: computes \(c_i {\longleftarrow} E(k, m_{ib})\) and sends \(c_i\) to \(\mathcal{A}\).

- \(\mathcal{A}\): outputs a bit \(\hat{b} \in \{0,1\}\).

Let \(W_b\) be the event that \(\mathcal{A}\) outputs \(1\) in \(E_b\). We define \(\mathcal{A}\)'s advantage wrt \(\mathcal{E} = (E, D)\) as below: \[ \text{CPA}\mathsf{adv}[\mathcal{A, E}] := | \Pr [W_0] - \Pr [W_1] |. \] Definition: IND-CPA security

CPA secure: \(\text{CPA}\mathsf{adv}[\mathcal{A, E}]\) is negligible.

Another way to define the attack game is by using "bit guessing". Instead of the challenger running 2 experiments and \(\mathcal{A}\) outputting \(\hat{b}\) twice, in this version, the challenger selects \(b \stackrel{\$}{\longleftarrow} \{0,1\}\) and only runs \(E_b\). The \(\mathcal{A}\) will output \(\hat{b}\) to guess the correct \(b\).

The advantage of \(\mathcal{A}\) in bit-guessing game is: \[ \text{CPA}\mathsf{adv}[\mathcal{A, E}]^{*} := | \Pr [\hat{b}=b] - 1/2 |. \] And the relationship between these two advantages is: \[ \text{CPA}\mathsf{adv}[\mathcal{A, E}] = 2 \cdot \text{CPA}\mathsf{adv}[\mathcal{A, E}]^{*}. \]

IND-CCA1 security (non-adaptive)

Below, the different CCA securities are defined in terms of public key encryption for later understanding of Fujisaki-Okamoto Transform.

An IND-CCA adversary has all the power of IND-CPA adversaries, plus a decryption oracle.

In Boneh & Shoup, their definition of IND-CCA security is the adaptive one, which is our IND-CCA2. We first give the IND-CCA1, though.

Attack Game and Definition: IND-CCA1 security in PKC

For a given public key encryption scheme \(\mathcal{E} = (G,E,D)\) defined over \((\mathcal{M,C})\), we define:

\(E_b\):

- Challenger: computes \((pk, sk) \stackrel{\$}{\longleftarrow} G()\).

- \(\mathcal{A}\): submits sequential

decryption queries to the challenger.

- The \(j\)th decryption query is random ciphertext \(\tilde{c_j}\).

- Challenger computes decryption results and sends to

\(\mathcal{A}\).

- The \(j\)th decryption result is \(\tilde{m_j} {\longleftarrow} D(k, \tilde{c_{j}})\).

- \(\mathcal{A}\): submits sequential

encryption queries to the challenger.

- The \(i\)th encryption query is a pair of messages \((m_{i0}, m_{i1})\in \mathcal{M}^2\) with same length.

- Challenger computes encryption results and sends to

\(\mathcal{A}\).

- The \(i\)th encryption result is \(c_i {\longleftarrow} E(k, m_{ib})\).

- \(\mathcal{A}\): outputs a bit \(\hat{b} \in \{0,1\}\).

Notice that step 2 and step 4, step 3 and step 5 can be done in parallel. (I'm not entirely sure about this, though.)

Let ... We define ... as below: \[ \text{CCA1}\mathsf{adv}[\mathcal{A, E}] := | \Pr [W_0] - \Pr [W_1] |. \]

IND-CCA1 secure: \(\text{CCA1}\mathsf{adv}[\mathcal{A, E}]\) is negligible.

IND-CCA2 security (adaptive)

We shall see the difference between non-adaptive IND-CCA1 and adaptive IND-CCA2.

Attack Game and Definition: IND-CCA2 security

For a given ... we define:

\(E_b\):

- Challenger: computes \((pk, sk) \stackrel{\$}{\longleftarrow} G()\).

- \(\mathcal{A}\): submits sequential

decryption queries to the challenger.

- The \(j\)th decryption query is random ciphertext \(\tilde{c_j}\).

- Challenger computes decryption results and sends to

\(\mathcal{A}\).

- The \(j\)th decryption result is \(\tilde{m_j} {\longleftarrow} D(k, \tilde{c_{j}})\).

- \(\mathcal{A}\): submits sequential

encryption queries to the challenger.

- The \(i\)th encryption query is a pair of messages \((m_{i0}, m_{i1})\in \mathcal{M}^2\) with same length.

- Challenger computes encryption results and sends to

\(\mathcal{A}\).

- The \(i\)th encryption result is \(c_i {\longleftarrow} E(k, m_{ib})\). Denote the set of all \(c_i\) as \(\mathcal{C}'\).

- \(\mathcal{A}\): submits sequential

decryption queries to the challenger

again.

- The \(k\)th decryption query is random ciphertext with restrictions \(\hat{c_k}\not\in \mathcal{C}'\).

- Challenger computes decryption results and sends to \(\mathcal{A}\) again.

- \(\mathcal{A}\): outputs a bit \(\hat{b} \in \{0,1\}\).

Line 6 and 7 are the added power of CCA2 adversary.

Advantage: \(\text{CCA2}\mathsf{adv}[\mathcal{A, E}] := | \Pr [W_0] - \Pr [W_1] |.\)

IND-CCA2 secure: \(\text{CCA2}\mathsf{adv}[\mathcal{A, E}]\) is negligible.

We can observe the difference from the attack game of CCA1 and CCA2. IND-CCA1 adversary can only choose random ciphertexts to submit as decryption queries, while IND-CCA2 adversary can decide what to be sent to the decryption oracle after \(\mathcal{A}\) knows the output ciphertexts \(\{c_i\}\) from the challenger.

IND-CCA3 security (authenticated)

Fewer literatures mentioned this one. For completeness, I put the reference link below. I'll skip this definition because this is quite out of the topic.

IND-1CCA security

There's also a definition for one-time CCA security. In attack game of IND-CCA2, if \(\mathcal{A}\) is restricted to make a single encryption query, we denote its advantage by \(\text{1CCA}\mathsf{adv}[\mathcal{A,E}]\). A PKE scheme \(\mathcal{E}\) is one-time semantically secure against CCA or simply 1CCA secure, if for all efficient \(\mathcal{A}\), the advantage \(\text{1CCA}\mathsf{adv}[\mathcal{A,E}]\) is negligible.

Concrete advantage \[ \text{CCA}\mathsf{adv}[\mathcal{A,E}] = Q_e \cdot \text{1CCA}\mathsf{adv}[\mathcal{B,E}] \] \(\mathcal{A}\): CCA adversary against \(\mathcal{E}\), makes at most \(Q_e\) encryption queries to challenger

\(\mathcal{B}\): 1CCA adversary against \(\mathcal{E}\)

Elementary wrapper: \(\mathcal{B}\) is an efficient interface interacting with \(\mathcal{A}\). My personal understanding of it is: \(\mathcal{A}\) against security property \(\mathsf{A}\) is at most as hard as a function of \(\mathcal{B}\) against security property \(\mathsf{B}\) under same assumptions.

Fujisaki-Okamoto Transform in ROM

In this section and the rest of the series, we will only focus on the property of public key cryptography.

An IND-CPA secure cryptographic scheme is often considered weak secure. Thus, there are several ways to transform an IND-CPA secure Public Key Encryption (PKE) scheme to IND-CCA secure scheme, such as:

- using a trapdoor function in ROM;

- using interactive CDH assumption in ROM;

- using DDH assumption in ROM

Fujisaki-Okamoto (FO) Transform is a generic way to transform any IND-CPA PKE to IND-CCA scheme in ROM. There is also a way without being in ROM, but that's too inefficient to be used.

The applications of FO transform are more related to Lattice-based and code-based cryptography schemes, such as LWE, NTRU, McEliece, etc.

Before we start to introduce FO transform, it is also important to define several security properties to understand FO transform.

One way, trapdoor function, and CCA secure encryption

One-wayness

Let \(H\) be a hash function over \(\mathcal{(M, T)}\). We define the advantage \(\text{OW}\mathsf{adv}[\mathcal{A, H}]\) of an adversary \(\mathcal{A}\) against the one-wayness of \(H\) as the probability of winning the following game:

- Challenger: chooses \(m\in\mathcal{M}\) at random and sends \(t := H(m)\) to \(\mathcal{A}\).

- \(\mathcal{A}\): outputs \(m' \in \mathcal{M}\) and wins if \(H(m')=t\).

\(H\) is onw-way if \(\text{OW}\mathsf{adv}[\mathcal{A, H}]\) is negligible for all efficient adversary \(\mathcal{A}\).

One-way function is easy to compute but hard to invert. We will also see the definition of one-way trapdoor function later.

2nd-preimage resistance

Let \(H\) be a hash function over \(\mathcal{(M, T)}\). We define the advantage \(\text{SPR}\mathsf{adv}[\mathcal{A, H}]\) of an adversary \(\mathcal{A}\) against the 2nd-preimage resistance of \(H\) as the probability of winning the following game:

- Challenger: chooses \(m\in\mathcal{M}\) at random and sends \(m\) to \(\mathcal{A}\).

- \(\mathcal{A}\): outputs \(m' \in \mathcal{M}\) and wins if \(H(m')=H(m)\) and \(m\neq m'\).

\(H\) is 2nd-preimage resistance if \(\text{SPR}\mathsf{adv}[\mathcal{A, H}]\) is negligible for all efficient adversary \(\mathcal{A}\).

Suppose: \(H\) is compressing (\(|\mathcal{M}|>|\mathcal{T}|\)), more specifically, \(|\mathcal{M}|\geq s\cdot |\mathcal{T}|\) for some compression factor \(s > 1\). If \(s\) is super-poly, then we have implications: \[ H \text{ is collision resistant} \Longrightarrow H \text{ is 2nd-preimage resistant} \Longrightarrow H \text{ is onw-way}. \]

One-way trapdoor function

Let \(\mathcal{X, Y}\) be finite sets. A trapdoor function scheme \(\mathcal{T}\) defined over \((\mathcal{X, Y})\) is a triple of algorithms \((G, F, I)\) where:

- \(G\) is a probabilistic KeyGen such that \((pk, sk) \stackrel{\$}{\longleftarrow} G(\cdot)\).

- \(F\) is a deterministic Encr such that \(y = F(pk, x)\), where \(x,y \in \mathcal{X,Y}\), respectively.

- \(I\) is a deterministic Decr such that \(x = I(sk, y)\), where \(x,y \in \mathcal{X,Y}\), respectively.

- Correctness property: for all possible \((pk, sk)\) from \(G(\cdot)\), and for all \(x\in \mathcal{X}\), we have \(I(sk, F(pk,x)) = x\).

Attack Game and Definition: One-way trapdoor function scheme

Given a trapdoor function scheme \(\mathcal{T} = (G,F,I)\) defined over \((\mathcal{X, Y})\), an adversary \(\mathcal{A}\), the game is as below:

- Challenger:

- computes \((pk, sk) \stackrel{\$}{\longleftarrow} G(\cdot)\);

- computes \(x \stackrel{\$}{\longleftarrow} \mathcal{X}\);

- computes \(y = F(pk, x)\);

- sends \((pk, y)\) to \(\mathcal{A}\).

- \(\mathcal{A}\): computes \(\hat{x} \in \mathcal{X}\).

The advantage of \(\mathcal{A}\) as \(\text{OW}\mathsf{adv}[\mathcal{A, T}]\) is the probability that \(\hat{x} = x\).

\(\mathcal{T}\) is one way if for all efficient \(\mathcal{A}\), \(\text{OW}\mathsf{adv}[\mathcal{A, T}]\) is negligible.

CCA secure scheme from TDF

A public key encryption (PKE) built from trapdoor function \(\mathcal{E}_{TDF}=(G,E,D)\) has several components below:

- A trapdoor function \(\mathcal{T}=(G,F,I)\) defined over \((\mathcal{X,Y})\)

- A symmetric cipher \(\mathcal{E}_s=(E_s, D_s)\) defined over \((\mathcal{K,M,C})\)

- A hash function \(H:\mathcal{X}\longrightarrow \mathcal{K}\)

Thus,

- Key generation: \(G\) in \(\mathcal{E}_{TDF}\) is \(G\) in \(\mathcal{T}\). The message space of \(\mathcal{E}_{TDF}\) is \(\mathcal{M}\).

- Encryption:

- \(E(pk,m):= x \stackrel{\$}{\longleftarrow} \mathcal{X}, y\longleftarrow F(pk,x), k\longleftarrow H(x), c\stackrel{\$}{\longleftarrow} E_s(k,m)\)

- output: \((y,c)\)

- Decryption:

- \(D(sk,(y,c)):=x\longleftarrow I(sk,y), k\longleftarrow H(x), m\longleftarrow D_s(k,c)\)

- output: \(m\)

- \(\mathcal{E}_{TDF}\) is defined over \((\mathcal{M,Y\times C})\)

If \(\mathcal{X} \neq \mathcal{Y}\), i.e. \(\mathcal{T}\) is not a trapdoor permutation, we need a modified \(\mathcal{E}'_{TDF}\) to construct CCA secure scheme. Basically, we change \(D\) to a \(D'\): \[ \begin{aligned} D'(sk,(y,c))&:=x\longleftarrow I(sk,y), \\ & \text{if: } F(pk,x)=y, \text{then: } k\longleftarrow H(x), m\longleftarrow D_s(k,c),\\ & \text{else: } m\longleftarrow \mathsf{reject},\\ & \text{output: } m. \end{aligned} \] If we model \(H\) as a ROM, \(\mathcal{E}'_{TDF}\) can be proved CCA secure. (I'll skip this. It can be seen in Boneh & Shoup Chapter 12.3.)

One-way trapdoor function even with image oracle (IOW)

Attack Game and Definition: IOW

For a ... the game:

- same with step 1 in OWTD

- \(\mathcal{A}\): submits image oracle queries to Challenger. Each query is of the form \(\hat{y} \in \mathcal{Y}\). If \(F(pk, I(sk, \hat{y}))=\hat{y}\), then Challenger sends "Yes"; else sends "No".

- \(\mathcal{A}\): computes \(\hat{x} \in \mathcal{X}\).

Advantage: \(\text{IOW}\mathsf{adv}[\mathcal{A, T}]\)

IOW, if negligible.

Every one way trapdoor function scheme can be easily converted into one that is one way given an image oracle.

Thm 12.2 from B and S Assume a hash function \(H: \mathcal{X}\longleftarrow \mathcal{K}\) is modelled as RO. If \(\mathcal{T}\) is \(\text{IOW}\), and \(\mathcal{E}_s\) is 1CCA secure, then \(\mathcal{E}'_{\text{TDF}}\) is CCA secure.

Concrete advantage \[ \text{1CCA}^\text{ro}\mathsf{adv}[\mathcal{A}, \mathcal{E}'_{\text{TDF}}] \leq 2 \cdot \text{IOW}\mathsf{adv}[\mathcal{B_{\text{iow}}, \mathcal{T}}] + \text{1CCA}\mathsf{adv}[\mathcal{B}_s, \mathcal{E}_s] \]

One-way encryption

Attack game: One-way encryption

Given PKE \(\mathcal{E}_a=(G_a,E_a,D_a)\) over message space and ciphertext space \((\mathcal{X,Y})\). Randomizer space \(\mathcal{R}\), adversary \(\mathcal{A}\).

- Challenger:

- computes

- \((pk,sk)\stackrel{\$}{\longleftarrow}G_a()\)

- \(x,r\stackrel{\$}{\longleftarrow}\mathcal{X,R}\)

- \(y\longleftarrow E_a(pk,x;r)\)

- sends \((pk,y)\) to \(\mathcal{A}\)

- computes

- \(\mathcal{A}\): ouput \(\hat{x}\in\mathcal{R}\)

If \(\hat{x}=x\) then \(\mathcal{A}\) wins. The probability of \(\mathcal{A}\) wining the game is \(\text{OW}\mathsf{adv}[\mathcal{A, E_a}]\). If \(\text{OW}\mathsf{adv}[\mathcal{A, E_a}]\) is negligible for all efficient \(\mathcal{A}\), we say \(\mathcal{E}_a\) is one-way.

Note: it's possible that \(\mathcal{A}\) doesn't even aware of the winning since \(\mathcal{E}_a\) may be probablistic.

Unpredictable encryption

\(\mathcal{E}_a, \mathcal{X,Y,R}\).

Say \(\mathcal{E}_a\) is \(\pmb{\epsilon}\)-unpredictable if for every possible \((pk,sk)\) from \(G_a\) and every \(y\in\mathcal{Y}\), a random \(r\stackrel{\$}{\longleftarrow}\mathcal{R}\), we have: \[ \Pr[E_a(pk,D_a(sk,y);r)=y]\leq\epsilon. \] We say \(\mathcal{E}_a\) is unpredictable for negligible \(\epsilon\).

Similar as one-way encryption to onewayness, unpredictable encryption can be seen as an instance for 2nd preimage resistance.

Fujisaki-Okamoto (FO) Transform: detailed construction

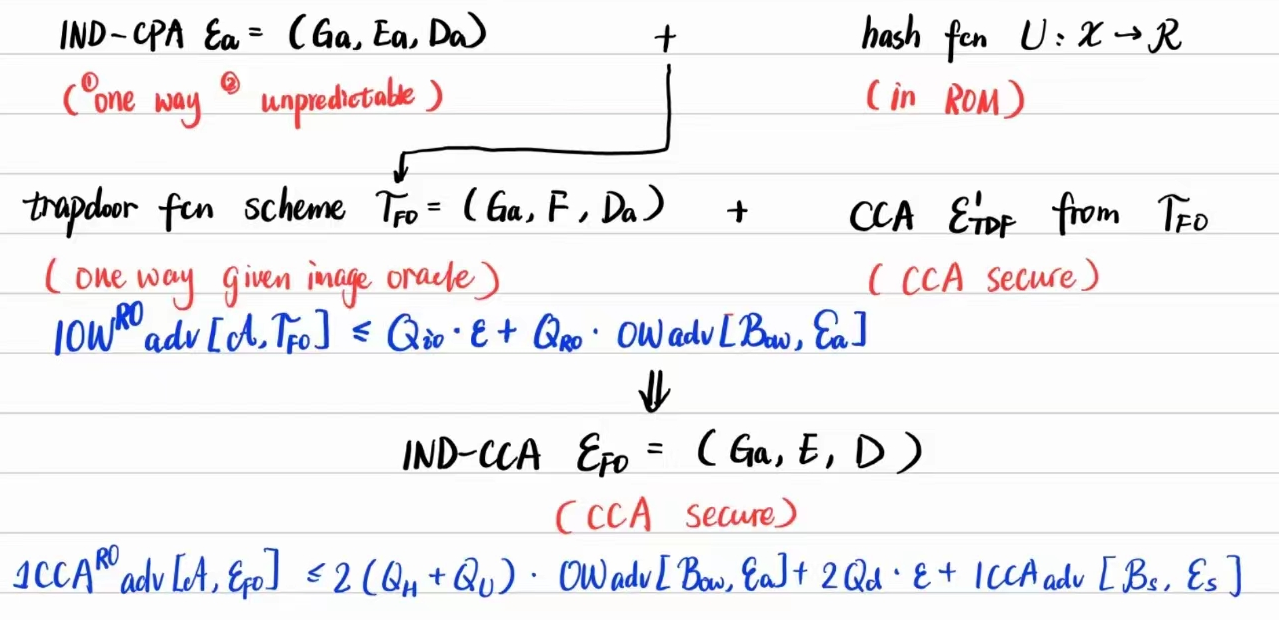

We start from an arbitrary IND-CPA secure PKE \(\mathcal{E}_a=(G_a,E_a,D_a)\) defined over \((\mathcal{X,Y})\). By introducing a hash function \(U: \mathcal{X} \longrightarrow \mathcal{R}\), we map a message \(x\in\mathcal{X}\) to a randomizer \(r\in\mathcal{R}\). In security proof, this hash function is modelled as ROM.

We can construct a trapdoor function \(\mathcal{T}_{\mathrm{FO}} = (G_a, F, D_a)\) from above, where \[ F(pk,x) := E_a(pk,x;U(x)). \] Now, we want to prove that \(\mathcal{T}_{\mathrm{FO}}\) is one way given an image oracle in the model where \(U\) is a ROM. First, we need 2 assumptions:

- \(\mathcal{E}_a\) is one way. Thus, given \(E_a(pk,x;r)\), it's hard to compute \(x\).

- \(\mathcal{E}_a\) is unpredictable. Thus, the probability of re-encryption of a ciphertext generating the same result will be negligible.

Thm 12.10 from B&S If 1️⃣ \(U\): ROM, 2️⃣ \(\mathcal{E}_a\): one way & unpredictable, then \(\mathcal{T}_{\mathrm{FO}}\) from FO transform (i.e. \(F(pk,x) := E_a(pk,x;U(x))\)) is one way given an image oracle.

Concrete advantage

Assume:

- \(\mathcal{E}_a\) is \({\epsilon}\)-unpredictable,

- \(\mathcal{A}\) attacks \(\mathcal{T}_{\text{FO}}\) in ROM in game

\(\text{IOW}\), makes at

most

- \(Q_{\text{io}}\) image oracle queries (query: \(\hat{y}\in\mathcal{Y}\), response: if \(F(pk, D_a(sk,y))=\hat{y}\))

- \(Q_{\text{ro}}\) random oracle queries (query: \(\hat{x}\in\mathcal{X}\), response: \(U(\hat{x})\)).

- \(\mathcal{A}\) always includes its output among its RO queries

Then \(\exists \mathcal{B}_{\text{ow}}\) against one-wayness of \(\mathcal{E}_a\) of game one-way encryption, where \(\mathcal{B}_{\text{ow}}\) is an elementary wrapper around \(\mathcal{A}\), such that: \[ \text{IOW}^\text{ro}\mathsf{adv}[\mathcal{A}, \mathcal{T}_{\text{FO}}] \leq Q_{\text{io}} \cdot \epsilon + Q_{\text{ro}}\cdot \text{OW}\mathsf{adv}[\mathcal{B_{\text{ow}}, E_a}] \]

The concrete proof can be seen in Boneh and Shoup ver 0.6 Ch12.6.

Finally, we look at how to get a CCA secure \(\mathcal{E}_{\text{FO}}=(G_a,E,D)\) over message space and ciphertext space \((\mathcal{M,Y\times C})\) from:

- A CPA secure PKE \(\mathcal{E}_a=(G_a,E_a,D_a)\) over message space, ciphertext space, and randomizer space \((\mathcal{X,Y,R})\);

- A symmetric cipher \(\mathcal{E}_s=(E_s,D_s)\) over key space and message space \((\mathcal{K,M})\);

- A hash function \(H:\mathcal{X}\longrightarrow \mathcal{R}\).

The constructionof CCA secure \(\mathcal{E}_{\text{FO}}\) is as below:

- \(G_a\): same as in \(\mathcal{E}_a\);

- Encryption scheme: \[ \begin{aligned} E(pk,m):= &x\stackrel{\$}{\longleftarrow}\mathcal{X}, r\longleftarrow U(x), y\longleftarrow E_a(pk,x;r),\\ & k\longleftarrow H(x), c\stackrel{\$}{\longleftarrow} E_s(k,m),\\ & \text{output: } (y,c); \end{aligned} \]

- Decryption scheme: \[ \begin{aligned} D(sk,(y,c)):= &x'{\longleftarrow}D_a(sk,y), r'\longleftarrow U(x),\\ & \text{if: } E_a(pk,x';r')\neq y, \\ &\qquad\text{then: } m\longleftarrow \mathsf{reject},\\ & \qquad \text{else: } k \longleftarrow H(x), m\longleftarrow D_s(k,c),\\ & \text{output: } m. \end{aligned} \]

Concrete advantage \[ \begin{aligned} \text{1CCA}^\text{ro}\mathsf{adv}[\mathcal{A}, \mathcal{E}_{\text{FO}}] &\leq 2\cdot (Q_{H}+Q_{U}) \cdot \text{OW}\mathsf{adv}[\mathcal{B_{\text{ow}}, E_a}] \\ &+ 2\cdot Q_d\cdot\epsilon \\ &+ \text{1CCA}\mathsf{adv}[\mathcal{B_s, E_s}] \end{aligned} \] LHS: advantage of \(\mathcal{A}\) against \(\mathcal{E}_{\text{FO}}\) in ROM wrt 1CCA property, makes at most \(Q_d\) decryption queries, \(Q_H\) random oracle queries of \(H\), \(Q_U\) random oracle queries of \(U\).

RHS: 1. advantage of \(\mathcal{B}_{\text{ow}}\) against \(\mathcal{E}_a\) wrt OW property 2. advantage of \(\mathcal{A}\) againast \(\epsilon\)-unpredictable 3. advantage of \(\mathcal{B}_{s}\) against \(\mathcal{E}_s\) wrt 1CCA property

At the end, we give a figure to summarize the "reduction" above.

Note

At the end of Part 1, we can see that comparing with MRM paper and the injectivity paper from my supervisors and me, the advantage from injectivity assumption is actually a elementary wrapper of the advantage from \(\epsilon\)-unpredictable assumption. But between them, there's still a long way left to walk through. This will be introduced in the next part of this paper reading series.

Reference

A Graduate Course in Applied Cryptography by Dan Boneh and Victor Shoup

- Chapter 3.11 A broader perspective: computational

indistinguishability

- Chapter 5.3 Semantic security against chosen plaintext

attack

- Chapter 8.10 Key derivation and the random oracle model

- Chapter 12 Chosen ciphertext secure public key encryption

- Chapter 3.11 A broader perspective: computational

indistinguishability

CS355 Lecture 3

Introduction to Security Reduction by Fuchun Guo, Susilo Willy, and Yi Mu

- 2.4 Further Reading

- 2.4 Further Reading

A Characterization of Authenticated-Encryption as a Form of Chosen-Ciphertext Security

What do the signature security abbreviations like EUF-CMA mean?